Yet the legal wrangle was but a mere itch in the divine comedy that is stardom. We didn’t know that even when Salman Khan had disappeared from the urban Indian’s imagination, in the smaller towns, if our sources are to believed, the Tere Naam haircut commanded a premium fee even as late as 2007.Īnyway, between the ostensible leaving and the providential return, Salman Khan off-screen was implicated in three high profile court cases, accusing him of hunting (2006), harassment (2002) and homicide (2002), respectively. In between the two Salman Khans was Tere Naam (2003), arguably his greatest performance, in which the eternal lover is severely punished for being in love and descends into what we now know as a legendary mad spell.

The one who returned was a killer, a vigilante.

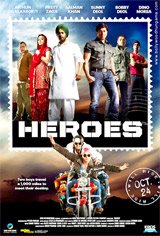

The one who left was a gentle lover, the eternal premi. The Salman Khan who left and the Salman Khan who came back were two different people. We watched Maine Pyar Kiya again recently, and then every film till he disappeared from the nation’s collective psyche after Kuch Kuch Hota Hai in 1998 and until he re-entered it with Wanted in 2009. Like in the year Maine Pyar Kiya was released, we weren’t old enough to think, but feel we did. We have been thinking about Salman Khan for the last few years some years more deeply than others. In a deux ex machina that would leave even the most ardent Bunuel fans impressed, we now have Salman Khan, aka Devi, in a police uniform, looking for Devil, aka Salman Khan in a black mask. The police officer is being replaced by a new one, an Inspector Devi Lal, who walks into frame in slow motion, giving enough time for our applause to rise and fall and rise again. In the closing scene of Kick (2014), arguably our favourite Salman Khan film, one that released in the closing days of editing our documentary Being Bhaijaan, police officer Himanshu Tyagi (Randeep Hooda) is being fired for not being able to capture his archenemy, Devil. Is a thing a thing by itself or does our sadhna make it so? Does the binary of heroes and villains defy our intuitive cultural notion of devotion, one that embraces and even celebrates infallibility? Samreen Farooqui and Shabani Hassanwalia, directors of the documentary Being Bhaijaan, look at the idea of Salman Khan through the eyes of his fans, and find that what they might be seeing is the archetypal idea of Shiva, the god that is beyond all good and evil. Read more by this writer Read more from this section They are currently working on a feature documentary on street dancing in the changing Delhi urbanscape, supported by the India Foundation for the Arts. It is the official selection at the New York Indian Film Festival, Film South Asia and Mumbai International Film Festival, 2015 and has been broadcast on Channel 4, UK. Their work on gender and sexuality involves Bioscope: Non-binary Conversations on Gender and Education (2013) and the feature length Being Bhaijaan, produced by PSBT. They have worked as associate directors and editors of Star by Dibakar Banerjee, as part of the Bombay Talkies omnibus, to celebrate the 100 years of Indian Cinema in 2013. Both the documentaries have been broadcast on Documentary 24X7 on NDTV. Their second feature Online and Available, released in 2012, told a story of an India-in-transition through its online identity formation and played at Mumbai International Film Festival, 2012. Their first feature documentary, Out of Thin Air, on Ladakhi local cinema was an official selection at International Film festival of Rotterdam and was the opening film at Film South Asia, 2009, besides playing at numerous other festivals. Samreen Farooqui and Shabani Hassanwalia founded Hit and Run Films in 2005, an independent video production unit, which engages with changing socio-political-personal realities through non-fiction cinema.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)